When they realized that every common flame retardant contained toxic chemicals, two University of Waterloo graduates Anneke van Hauven and Elias Trouyet were inspired to create a revolutionary green and safe solution — a non-toxic flame retardant made out of seaweed.

What started out as a fourth-year engineering design project has grown into an incorporated business. Their innovation was awarded this August, as they were announced as runner-ups for the James Dyson Award, which recognizes young engineers and designers with problem-solving ideas.

Flame retardants are chemical compounds that prevent both the ignition and spread of fire on the materials they are applied to. They are required for many industrial and consumer products.

While flame retardants are an essential part of fire safety, most have long-term health impacts, as they are known to cause cases of infertility and cancer, as well as inhibit brain development in children. Flame retardants are also toxic to the environment. The largest market group of flame retardants is currently brominated flame retardants, which are considered not only toxic but also persistent and bioaccumulative, meaning they accumulate up the food chain as smaller prey are consumed by larger predators. When larger prey consumes many contaminated smaller prey, they are exposed to a higher concentration of the contaminant.

Van Hauven and Trouyet’s solution uses a biopolymer made from seaweed, which is a natural flame retardant. Seaweed has a tightly packed cellular makeup, which makes it fireproof, and with the amount of seaweed in the world’s oceans increasing due to an abundance of nitrogen caused by climate change, this is an ideal sustainable design material. Van Hauven says, “there is already an abundance of seaweed and it’s causing problems for locals in warmer climate areas, so the idea was to turn something that’s a nuisance into something good.”

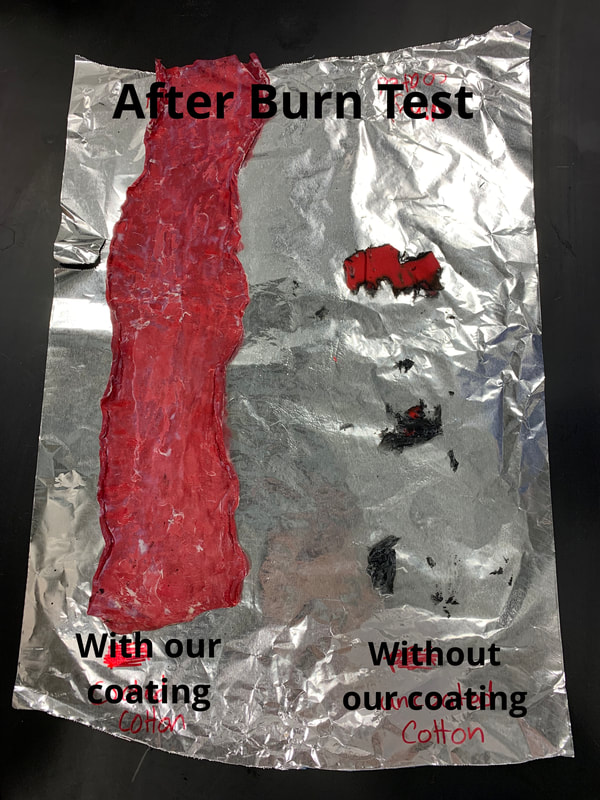

This polymer is then embedded with nanoparticles that work to provide flame resistance by both delaying the combustion reaction and extinguishing the ignited material. To apply the polymer, textiles are dipped and submerged in the gel coating. Van Hauven and Trouyet formulated two different coating options, both of which surpass the industry standard flame retardancy level, with a burn rate that is 10 times better than the requirement, according to their profile on the James Dyson Award site.

For the first eight to twelve months, the project was purely research based, which van Hauven attributes to the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. In just the last four months, the team has been able to start testing their research, and they were pleasantly surprised by the almost immediate success. “Theoretically it is supposed to work, but sometimes research doesn’t translate into reality,” says van Hauven. In an interview with iHeartRadio, they also said they turned to their co-founder and asked, “are we doing this right?” because they, “were just shocked.”

When compared to current flame retardants, this solution offers three major advantages. For one, it is non-toxic, which is beneficial for both consumers and the environment. The product is also likely to save consumers money in the long run, as a number of flame retardants are being banned by the government as regulations increase. When these flame retardants are banned, consumers are required to discontinue use of the flame retardant, which can result in money wasted on unused products. With a flame retardant that is non-toxic, this would be much less of a concern. Lastly, the product is sustainable and made from renewable resources, which alleviates the negative impact that current flame retardants have on the environment.

Van Hauven and Trouyet have big plans for the future of AlgoBio. First, they will be re-examining the current technology, making sure to meet six important objectives outlined on their website, including good flame retardancy, being non-harmful to humans or the environment, having good physical properties, ability to be easily disposed of, and being cost effective and scalable. They believe these goals are achievable, and think that, with some slight modifications, the product could be applied as an additive, instead of just a coating, for big industries like plastic and rubber. The pair is also interested in pursuing fire protection for firefighters. AlgoBio has also applied to Velocity and hopes to take on co-op students in the future.

When asked how AlgoBio could inspire other students who have big ideas and are questioning if they should pursue them, van Hauven said, “be sure you find something you love and really want to work on. Find something you believe would take off and get exposure to being an entrepreneur.”

You can follow AlgoBio’s journey via their website or LinkedIn.