By: Stephanie LResources and funding as opposed to awareness, are needed to break mental illness stigma

By: Stephanie LResources and funding as opposed to awareness, are needed to break mental illness stigma

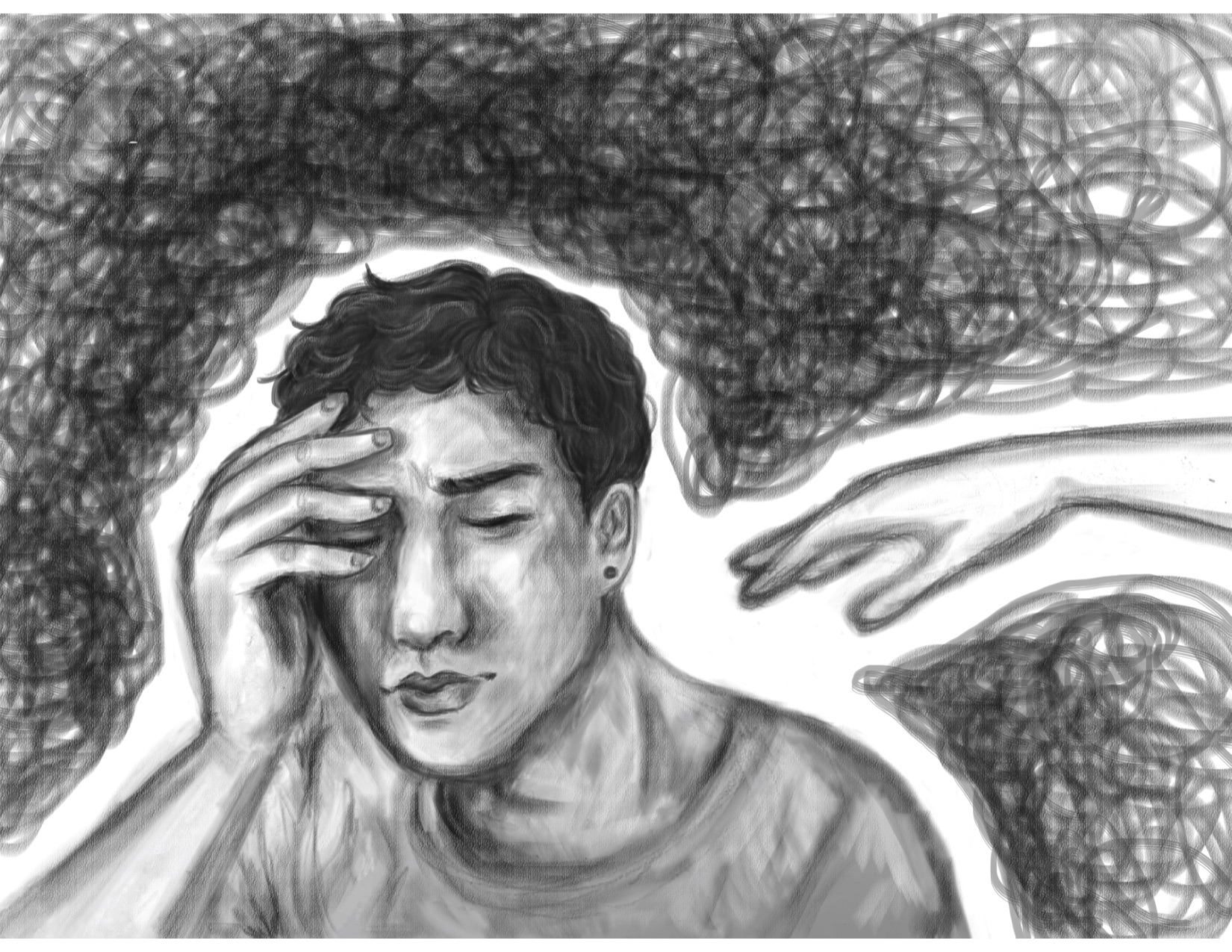

Mental illness affects one in three Canadians at some point in their lives. Chances are, you have either been personally affected or know someone who has been personally affected by a mental health condition. Despite how prevalent mental health problems are in our society, less than half of individuals with mental illness actually receive mental health care when they need it. That means that the majority of people don’t ever get the appropriate care they need.

There are several reasons for this. One is lack of awareness on the topic. Often, people are nervous about the stigma surrounding mental illness. Not only are people afraid of what others will think of them and the possible discrimination they may face if they open up about their issues, but oftentimes, people believe that admitting that they are having mental health problems is a sign of weakness and believe they should be able to “handle things” better.

I can assure you that mental illness has a unique way of making an individual downplay their symptoms, making them believe that they don’t deserve help because “others have it worse” or their problems aren’t “that bad.”

There have been some initiatives put in place to help build people’s knowledge and awareness on mental health. These are a start, and better than doing nothing at all; however, more often than not these are only Band-Aid solutions. They allocate certain days to open conversation and to create a welcoming space for those who experience mental health problems. A few days a year where people don’t avoid the topic completely.

Bell Let’s Talk Day, National Suicide Prevention Day, and other awareness campains only do so much. These are days to make people feel good, like they are being supportive of people suffering from mental illness, but research has shown that they do not change long-term behaviour. Every day should be a day where people feel comfortable talking about mental illness, and these campaigns do little to help on the other 364 days of the year.

In the past couple years self-care has been a large focus. Self-care is great. I’m all for it. But self-care is a lot more than handing out kits filled with positive messages, face masks, and colouring books. It’s hard to speak out against these programs that are trying to raise awareness and eliminate stigma, but these “self-care kits” do very little to help people who are waiting for up to a year to receive services, or who have lost services due to recent budget cuts, or who can’t afford necessary medication or the intensive therapy that they need.

We don’t need more awareness per se, we need more resources, more funding, and more people who care about helping people. A recent article by CBC stated that the wait times in the Waterloo-Wellington area can be up to a year. This is for agencies such as the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) who offer free or low-cost services.

Clinics that offer free or subsidized psychotherapy can have month long waiting lists, and private psychologists, on average, charge around $100 for an hour-long session. Psychologists are not covered by provincial insurance. This creates a divide between people who can afford services, and those who rely on OHIP or other provincially covered options. Individuals who can afford private care are able to be seen relatively quickly, and those who are unable to cover the costs are left waiting for far too long. The average waitlist for adult mental health counselling & treatment is 118 days, according to CMHA.

Many specialized programs offered through the province, such as dialectical behaviour therapy groups, early psychosis intervention programs, and groups for individuals with recurrent suicidal ideation have wait times of almost a year.

The four OHIP covered options for residential eating disorder care in the province have wait lists of up to ten months. This time varies between programs and because patients are triaged based on their illness severity, which is often determined using body mass index (BMI), and leaves some people waiting longer than others. Treatment at Homewood, Ontario’s private addiction and eating disorder recovery centre, costs around $250 a night, and the waitlist for the people who can pay for treatment is around two weeks, which is far less than the provincially funded resources.

The similarity between these different provincially funded programs is that they all have limited resources, which makes them unable to provide the necessary level of care to their patients. There are no options for a lot of people who are in need, and people are dying because they are unable to receive the treatment necessary to help them regain their lives back.

So, please, take back your face masks, fidget spinners, and funds used to promote these days geared towards “awareness” of the issue, and put it toward funding the programs and resources that individuals actually need to survive.