No political party won the majority of power in the Canadian federal election for the first time since 2008.

Canadians collectively gave Justin Trudeau’s Liberals a slap on the wrist in this election, making him walk the tightrope that is a minority government.

That means the political games are just beginning.

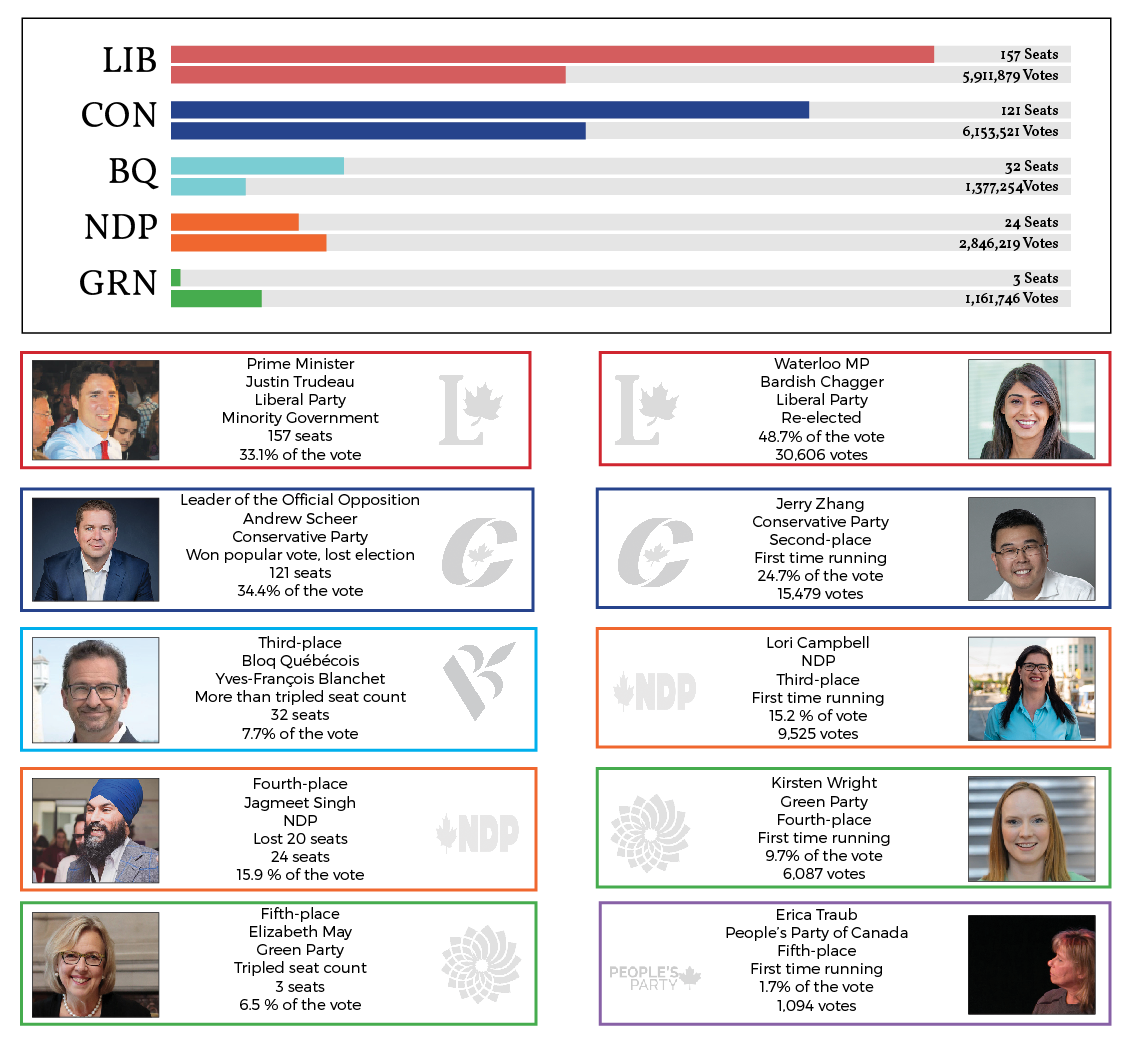

The Liberal party won 156 seats in the House of Commons on October 21, and while that’s more than any other individual party, it’s not the 170 seats needed to hold majority power in Canada’s 338-seat parliament.

While the Conservatives’ Andrew Scheer won the popular vote, 34.4 per cent to the Liberal’s 31.1 per cent, Canada’s First Past the Post electoral system rewards “plurality” not votes.

In other words, once a party is the bigger than any individual party in its electoral riding, votes don’t matter anymore.

The last time a government held power with such a low percentage of the vote in Canada was when John A. McDonald won in 1867.

But Stephen Harper’s Conservatives were close in 2006, winning a minority government with just 36 per cent.

The Bloc Québécois were rewarded by Canada’s electoral system this time around, winning 1.2 per cent more of the vote than the Green Party, but ten times as many seats in the House of Commons.

Though the NDP had a disastrous night electorally, losing 20 seats, they’re actually in a stronger position than they were following the 2015 election.

That’s because the new minority Liberal government needs 13 votes from somewhere outside its party to pass anything.

While Trudeau could try to coax the Conservatives or Bloc to support them, the NDP is far more likely to work with the Liberals on legislation.

Because of that, the NDP actually hold the balance of power in the House of Commons, despite being the fourth-place party.

Though the New Democrats won’t get everything they want out of the Liberals, they’re demands in the event of a coalition included pharmacare coverage, dental care coverage, housing investment and eliminating interest on student loans.

Those policies could make their way into Liberal legislation to earn the support of the NDP.

Just like his father in 1972, Justin Trudeau’s second election campaign was fraught with unforced errors that drove support to opposition parties only four years after Trudeaumania 2.0.

Another parallel to 1972 is the NDP supporting the Liberals in an unofficial capacity, as David Lewis did to Pierre Trudeau.

That alliance lasted two years before another election was called, and Canadians should prepare for that possibility in the years to come.

The biggest risk of sitting as a minority government is opposition parties can overthrow the governing party, in this case the Liberals.

If the opposition parties defeat Trudeau on a budget bill, where the government outlines how they’d spend taxpayer money, the opposition parties can try to pass a motion of “non-confidence” in the government.

If it the government is defeated, Canadians will have to go back to the polls.

Minority governments were kicked out of power by a non-confidence motion in 2004, when Paul Martin’s Liberals were ousted, and to Stephen Harper’s Conservatives in 2006.

Harper’s second minority government almost fell to a non-confidence motion in 2008, but the then-prime minister shut down parliament and called an election himself to avoid embarrassment.

In both 2008 and in 1972, a short lived minority government that was propped up by opposition parties led to a majority government before the end of the term.

The 2019 election starkly contrasts the Liberal’s sweep to power in 2015.

The Canadian electoral map is now more divided than it has been in over a decade.

If you like elections and political horse trading, you’re in for a treat.