In conjunction with Holocaust Education Week, Hillel Waterloo, a student club centred on Jewish life, brought the stories of two Holocaust survivors to campus.

“We wanted to do something different this year for Holocaust Education Week, so we came up with this idea of doing an exhibit and doing something that would both embody what it means to never forget and bring a sense of education to people on campus so that they could learn something new about the Holocaust,” Jeremy Spira, co-chair of Hillel Waterloo, said. “We also thought it would be important to bring a survivor to campus because it’s one thing to have an exhibit, but it’s another thing to talk about their experience and not just read through documentation.”

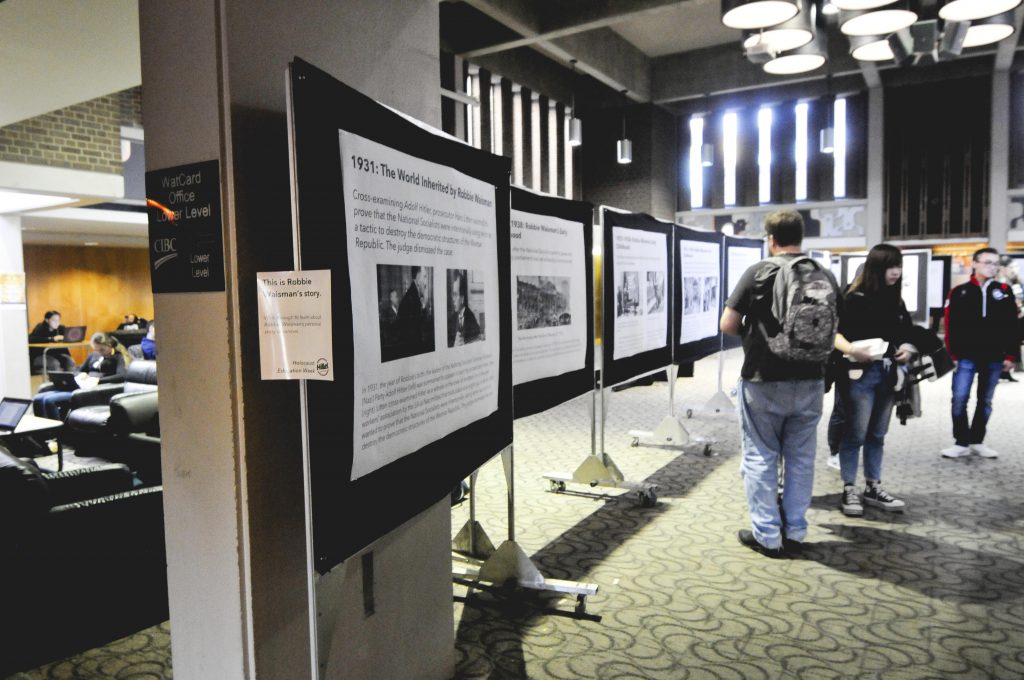

To begin Holocaust Education Week, Hillel Waterloo held a narrative exhibit in the SLC Great Hall on Nov. 7. The exhibition was laid out to create a path from one end of the Great Hall to the other.

One side of the path told the story of Robbie Waisman, a Holocaust survivor from Skarsysko, Poland. Waisman was eight when his city was bombed and occupied in 1939. He was sent to live on a farm with a non-Jewish family in 1940, but ran away to the ghetto formed in Skarszyko right before the police started offering sugar and flour as a reward for turning in Jewish children. In 1941, Waisman was smuggled out of the ghetto by his brother when the brother caught wind that they would be transported to Treblinka, where fatal gassing occured. Waisman was liberated from Bunchenwald in 1945, but was told he could not go home. Waisman wrote that he “could not understand why people, other than the Nazis, wanted to kill us,” when he was told it was dangerous to go back. In the end, he immigrated to Canada.

The other side of the path told the story of the Holocaust. The path started in 1931, when a lawyer named Hans Litten did a cross-examination of Hitler for using terror to destroy the democratic structures of the Weimar Republic but was dismissed. The Nazis gained full power Feb. 27, 1933 when the Reich-tag fire happened. It went on to describe the Night of Broken Glass in 1938 to the deportation of Jews in 1941. The path ended 1945-1948 when the world finally came to terms with the atrocity.

“For us, the exhibit was about trying to demonstrate to people what six million lives look like, and it’s important to realize every life has a story,” Spira said. “When we talk about the Holocaust, it’s not just six million Jews, 1.5 million children, it’s more than that. These were people, these were stories that were never told.”

Hillel Waterloo also invited Holocaust survivor Paula Goldhar to speak about her experiences as a Holocaust survivor on Nov. 9. Goldhar recounted her story of the beginning of the war and living in the ghetto of a small town.

“It was a ghetto without walls because the Germans could not erect walls in every single town and village. The only way you knew it was a ghetto was because you could not go out of city limits. Somebody went outside the city limits, you didn’t [see] them again,” Goldhar said. “Life was getting harder in the ghetto because … it was a little town, there was nothing to do there, food was very scarce, we were dying … and of course, we could not leave so we waited until they brought some food for us.”

During the war, Goldhar was separated from her family and was sent to work in an ammunition factory.

“1942 in October, they came in early morning, came in some German buses … and they announced that all the young people should come out of their little homes … they wanted them to go to work for the Germans,” Goldhar said. “We didn’t want to go because our parents were old … but we did because our father made us.”

In 1945, the Germans ended their occupation of the camp. Goldhar and the other survivors left the camp and ended up in a city where Goldhar was reunited with her brother and her sister.

After sharing her story, Goldhar shared photos of her family from before and after the Holocaust which her brother kept on him the whole time.

“I couldn’t believe when I saw those pictures. He had them taped to his chest and when he went to the showers, he gave them to a friend,” Goldhar said.

Spira remarked that it is important to hear Holocaust survivor stories because “it’s something that happened not long ago … and if [we] don’t hear Holocaust survivor’s stories, then history is bound to repeat itself.”