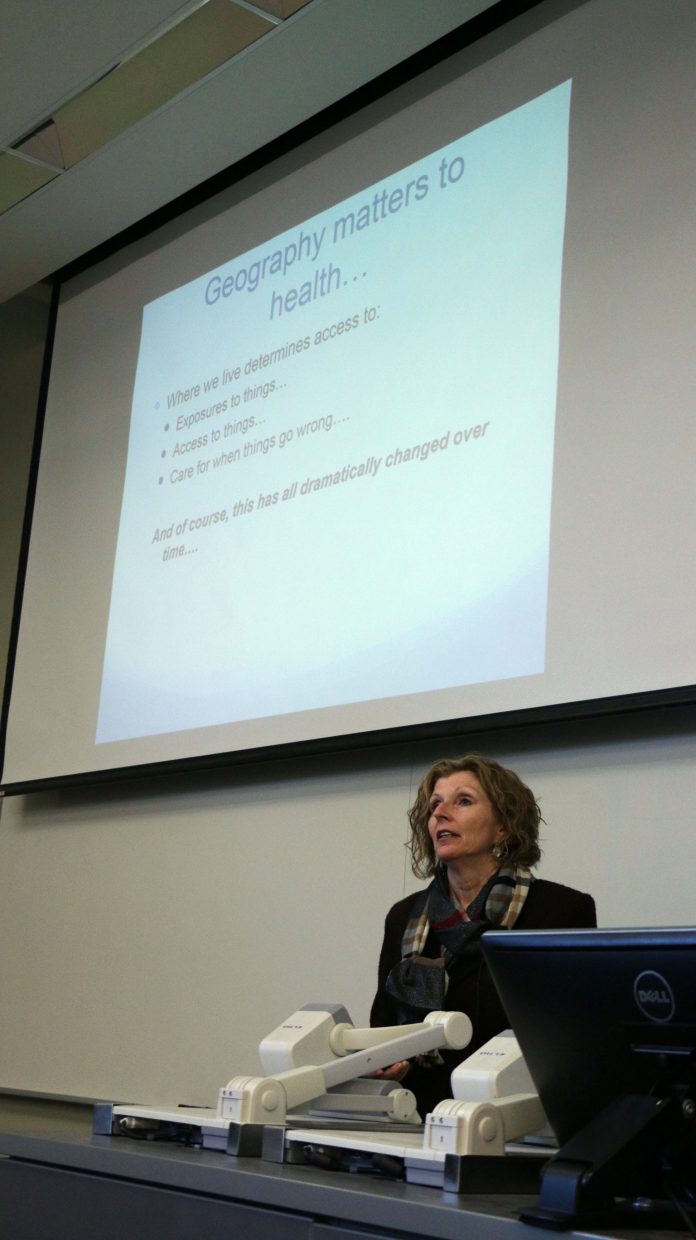

As part of the ongoing Knowledge Integration Seminar Series, Dr. Susan Elliot held a seminar on Jan. 6 connecting two fields that might not seem to have much in common: geography and medicine.

“Usually when I say I’m a medical geographer, people say ‘What? Huh?’” Elliot joked as she introduced her research field.

Medical geography, as Elliot described it, is “the study of the distribution, diffusion, determinance, and delivery of health and health care.” Despite it being an uncommon field, it is extremely valuable to the medical profession, to which Elliot’s long and prestigious career can attest.

Over the years, Elliot has worked as the director of the Institute of Environment and Health at McMaster, a senior research fellow in the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, and the University of Waterloo’s own dean of health sciences, among other positions. She is also involved in wide-scale research, and works as a principal investigator for the National Food Allergy Strategy of Canada and the Global Index of Wellbeing, as well an appointed member of the Health Canada Food Expert Advisory Committee.

“Where we live also determines our access to things,” Elliot said, explaining the connection between geography and medicine. “We have a literature within health geography that talks about ‘food deserts.’ When you go into inner-city areas in large cities, it’s very difficult to find a grocery store, fresh fruits and vegetables, those sorts of things, you won’t find them. You’ll find convenience stores that overprice things, charge a lot of money, and don’t buy a lot of fresh produce. Where I live gives me access to things, for good or for bad.”

“It also gives me access to things for care, for when things go wrong,” Elliot continued. “In Canada we have universal access to health care, free of financial barriers. But we don’t have access free of geographic barriers. For example, you cannot get an abortion in Prince Edward Island. Also, imagine if you are living in a remote community in the north, and you can’t get access to health care — a doctor won’t go and work there — and you have cancer and need treatment. Or you’re a high-risk pregnancy and have to be flown south, down to Edmonton or Ottawa.”

To illustrate the many ways geography (specifically, both physical and social environments) create differences in medicine, Elliot discussed one field of research she is heavily involved in: allergies. For example, though food allergies affect 7.5 per cent of Canadians in total, they are more common in different groups of Canadians. After organizing an updated national survey which accounted for proper representation of low-income and Canadian immigrants, Elliot found that allergies were less common among Canadian immigrants than Canada-born residents, particularly immigrants who had been in the country for less than 10 years.

Elliot also noted that the severity of allergies in Canada is so different from many other countries that many immigrants have trouble believing claims of how dangerous they are.

“[Allergies are] not a primary health concern for immigrants, they’re often surprised or skeptical about their severity,” Elliot said.

Elliot also noted an under-reporting of allergies among low-income and non-reserve Aboriginal families, possibly due to the expensive costs of EpiPens or limited access to health care in general.

To bridge the gaps in allergy understanding among Canadians, Elliot is working with AllerGen, a national centre of excellence (“a group of scientists and graduate students who come together to try to solve a problem,” as Elliot explained) oriented towards creating publicly significant impacts on the treatment of food allergies. Elliot herself is responsible for creating a national food allergy strategy, a large-scale ongoing project involving many universities and highly-qualified personnel. While still in a relatively early stage, Elliot’s work involves connecting researchers with stakeholders and people affected by allergy research, in order to translate the researcher’s findings into practical applications to treat allergies.

“It’s going to be very complicated,” Elliot said. “But nobody’s ever done this before, and that’s the fun thing about doing research — you get to do things nobody’s ever done before. It could be a huge disaster, it could be really cool.”