Universities can feel like their own little world. It is easy for those who study, live and work on campus to get lost in this world. However, when thinking about climate change, a much bigger perspective is needed. Our actions, both positive and negative, all feed into the global impacts the world is facing. So, what should the University of Waterloo be doing when it comes to climate change?

“A lot of people think of climate change as a technical, scientific issue, but I see it as both that and as an issue of systems and justice in society and culture. A lot of the culture of who we are is founded in our institutions [which] are forming the culture of how we as humanity see our role in climate change and how we understand climate change and the impact and the moral imperative to deal with it. Universities have the opportunity to form the cultural understanding of who we are that guides policy and guides individual actions and guides the ability for organizations like ours to actually make a difference,” said Tova Davidson, Executive Director, Sustainable Waterloo Region.

With tens of thousands of students and staff, UW is a large source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. UW has a commitment to integrating sustainability practices into campus operations and culture. As an academic institution, UW also has an extensive focus on climate research and education. Still, throughout the University community, people are pushing for more.

“Our students and our employees want to see change, [they] want to see the university improve. And we reflect really critically on that. I think there is certainly external pressure from across society,” said Mathew Thijssen, UW’s Director of Sustainability.

Imprint is taking a look at UW’s plans to tackle climate change and become more sustainable, including how the University’s actions compare to those taken by other schools as well as the actions scientists believe are necessary to effectively address the climate crisis.

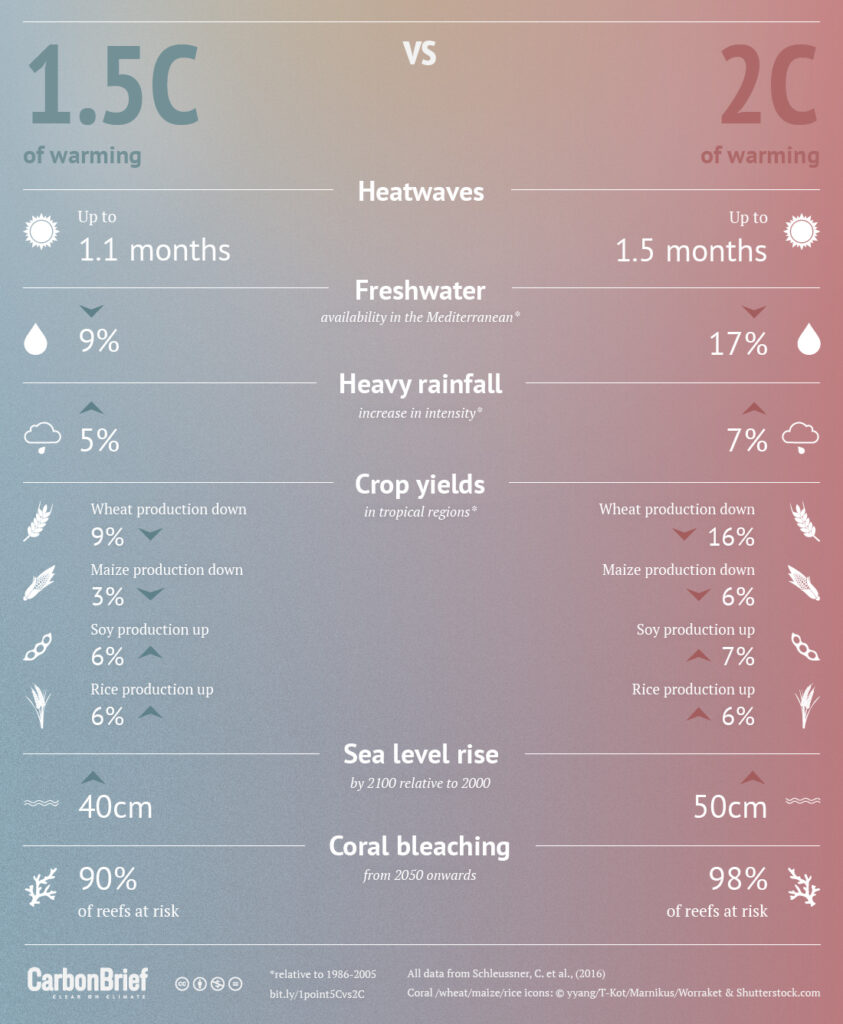

When it comes to reducing emissions and mitigating climate change, there are many numbers, commitments and targets floating out there. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a body of scientists who work to bring together research on climate change, says the world should be limiting warming to 1.5 C to avoid some of the bigger impacts of climate change. On Dec. 12, 2015, the Paris Agreement was signed setting the world’s climate target at limiting warming to 2 C with an aim to keep it below 1.5 C.

That seems like a simple enough way to establish what UW should be doing, but the agreement is based on voluntary commitments by nations. Canada’s latest commitment to the Paris Agreement is to reduce emissions by at least 40-45 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. According to the Climate Action Tracker, this target still falls short of the at least 54 per cent domestic reduction needed to meet the Paris objectives, earning Canada a rating of “Almost Sufficient” on the Climate Tracker.

If that seems complicated, it is also important to consider historical responsibility when determining fair share. GHG emissions have been accumulating for over a century and these emissions are still having an impact today. In fact, past emissions have already caused about one degree of warming in the atmosphere.

Because industrialization, which is responsible for most of the GHG emissions, has not happened evenly over that time, and because our emissions are still not globally distributed proportionally, should we take into account not just the emissions we are producing today, but also those that we have emitted for over 150 years? Should we also take into account the size of our population?

When we take historical responsibility into account, Canada does not fare well. According to the Global Carbon Atlas, Canada was the 11th worst emitter in 2020. When we look at historical responsibility, Canada ranks 10th in an analysis of emissions from 1850 to 2021 by Carbon Brief. When population is taken into account, Canada ranks first among emitters when dividing the emissions by today’s population and second when dividing by the historical population.

The consequences of even minimal increases in global temperatures are drastic. Climate change has already caused numerous extreme weather events, food and water shortages, mass extinctions, widespread disease and many other problems. If current trends continue, these issues, and the social and economic repercussions they bring, will become much worse.

With all of this in mind, what should UW strive to achieve?

“I’d say their responsibility is to do as much as they can,” said Michaela Smitas-Kraas, fourth-year ERS student.

With over 40,000 people forming part of the UW community, Jenna Phillips, the WUSA sustainability Commissioner, believes UW’s efforts must come both at an infrastructural level and a behavioural level.

“On an infrastructure sense, in terms of what we do on campus and where we can really be focusing on our climate change mitigation efforts, we should be investing in green buildings or net-zero buildings or more greenery on campus that can absorb carbon emissions. We should be thinking about the carbon impact of those types of activities as well as other things like food waste, or other waste or transportation related to campus activities,” she said.

“The other piece is behavioral. How can we be motivating staff, students and faculties to be taking action in their own lives to reduce their impacts related to climate change? That can be through education and training, social media campaigns and other ways we can be influencing student behaviors. We should also be integrating that into our policies and our plans that shape how the university operates at an institutional level because that will show that climate action and carbon emissions reduction is a priority for the university. The only way to really solidify that is through policy change and incorporating that into our strategic plan.”

Davidson agrees. “There are two roles universities play: one is the education of people and the other is research and progress. And I think those two things fit really well. But I think we also need to bring them together [to give] students opportunities to actually affect change and understand how to change systems,” she said.

According to Thijssen, when UW is determining their responsibility, they take many targets and factors like the IPCC findings, the Paris Agreement and other scientific information into account.

“We saw again yesterday another report released from the UN on the IPCC tracking the urgency of taking action and the accelerating risks of not taking action fast enough. We use the science-based target initiatives [such as those that have been established through the Paris Agreement] to help us in the design of our short, medium and long term targets for our own action plan,” he said.

The University’s current targets for emissions reductions are a 17.5 per cent reduction by 2025, a 35 per cent reduction by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050.

“Whatever we do on campus is a drop in the bigger global bucket, but it’s important that we do it. [For example] we have researchers who are authors on the IPCC reports to make sure that our expertise is contributing to these global challenges and aligning global effort with the science,” Thijssen said. “We’re planning for the long term that the physical campus of the future is aligned with these low carbon, highly sustainable, highly efficient targets.”

However, UW’s short- and medium-term targets are currently below Canada’s commitments to the Paris Agreement and what is scientifically required to stay below even just 2 C of warming.

https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/canada/

http://www.globalcarbonatlas.org/en/CO2-emissions

https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-which-countries-are-historically-responsible-for-climate-change