The practice of banning books has its roots in various cultures and locations. Today, these books are celebrated to ensure access to information for all.

Librarian and curator of the special collections and archives Jessica Blackwell sat down to talked to Imprint about the history of banned books. Blackwell has been working at Dana Porter for four years, doing all the programming for the rare book collection.

“We wanted to do something for Banned Books Week because we think it’s important to support freedom of access to information,” said Blackwell.

Blackwell continued, “[It’s important to acknowledge the books that have been or were banned] because censorship still happens, which is something we don’t think about living in Canada. We often think we are free and books aren’t challenged here. There are many books challenged in school districts — parents deem work offensive or think that their kids shouldn’t have access to it — which limits the access of information a large variety of people have.”

When books are challenged, they are put under review to be put in a different section of the library, but they aren’t completely removed. However, according to Dr. Jennifer Harris of the UW English department, one book that you still won’t find in any public library in Toronto is Flowers in the Attic.

Blackwell remembered when she was younger her teacher taught a book that was being challenged at the time, Thomas’ Snowsuit by Robert Munsch. The story features two teachers, one who identifies as male and one who identifies as female, who change clothes through the course of the book. People believed this would promote cross-dressing to children and therefore challenged it. The library did not take this challenge seriously and instead of reviewing the case, they put the book on display and promoted it. Blackwell said, “[It is important] to think about why something is being challenged and not just agreeing with it.”

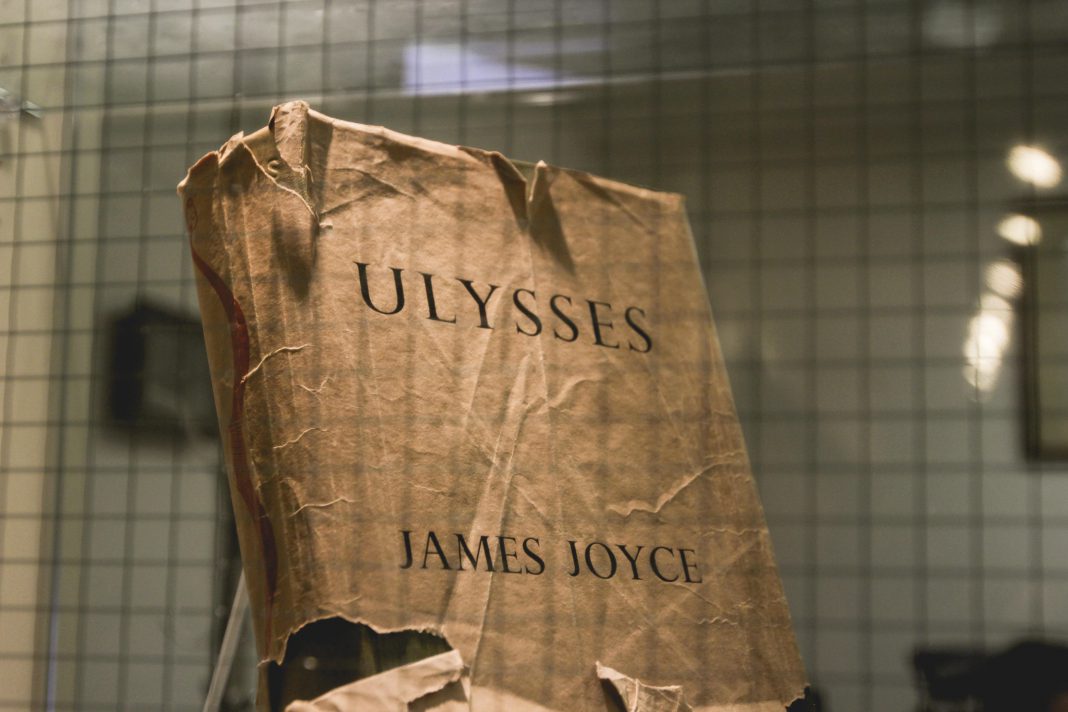

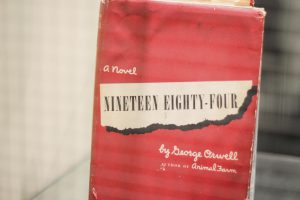

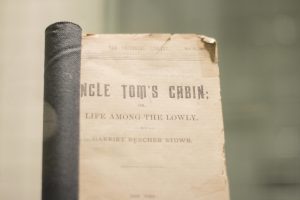

Dana Porter Library had many books on display through the month including, Ulysses, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Tarzan (because Tarzan and Jane were living together before they were married), The Scarlet Letter, 1984, Mein Kampf (for obvious reasons), Little Red Riding Hood (because she was carrying wine to her grandmother) and Fanny Hill.

Fanny Hill was written in 1754, the first prose porn book, which is why it was banned. In 1954, Dana Porter, who was the chief justice of the Ontario court of appeal, struck down the ban.

Blackwell commented that the practice was probably started in the Vatican as a religious practice condemning scientific texts that went against the teachings of the Bible.

Harris has taught banned books including Moby Dick, The Scarlet Letter, and Harry Potter. “As a teacher of literature its impossible to avoid it … everything from the Canterbury Tales to Moby Dick has been banned [at some point]. [Banned books] reflect where a society is at. Books that that are challenged are often challenged based on values. Someone is making a presumption [about some values]. Often banned texts contain critiques by marginalized people.”

Harris added that in libraries and bookstores books are divided by age, “You won’t find 50 Shades [of Grey] in the kids section.” Canada has laws against hate speech, which causes people to “shy away from outright bans,” but there are some authors that can’t be published in Canada.” One example of this is books denying the holocaust.

Harris shared that LGBTQ* bookstores have historically had a hard time getting literature on their shelves. “We had the RCMP doing moral policing at the border so some books didn’t even make it into the country. The heart of the matter is: who decides what is acceptable, and what is moral?” she said.

For a long time, books that featured homosexuality were not allowed to be sold, shared, or at the library unless the characters that were homosexual died a horrible death, “but now the books show them being happy, and so it’s a problem,” Dr. Harris said, “There’s a kind of irony there. Challenges often come when work is promoting homosexuality.”

The history of banning books has evolved as a community-based activity and “happens differently in different countries” such as book burnings in Nazi Germany or the Comstock laws in the U.S. “Generally [this happens] when people are responding to authority, so we see these kinds of things happening at times of significant social conflict. On the flip side people want to ban Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for the use of the ‘N word’,” said Harris, “Huckleberry Finn was never meant for kids. People still don’t know how to talk about race and teachers are not trained to have these sophisticated talks with 15-year-olds.”

One series that everyone knows has had a long history of challenges is Harry Potter. “[The series was challenged by the] Evangelical Christians in the U.S. The challenges emerged before the series was done because people thought there was content going against Christian teachings. It is still challenged because people feel it promotes demon worshipping, witchcraft, and engaging with the dark arts. Some of these people have come around … [they] saw important messages, like, standing up to authority as a marginalized group, but that is also why it is challenged,” said Harris.

Harris also shared, “People who challenge these books, come out and say that they will not read this ‘trash’.”

“I am an Americanist by training. They [the U.S.] engaged [in banning books] by only having one press, which is now the Harvard Press, and the ministers controlled it. Anything that was printed had to be signed off on by a body of ministers … [this was a kind of] pre-emptive banning. There are all kinds of interesting critiques that never made it to print [because of this],” said Harris.

“The minute you ban a book everyone knows what that book is,” Harris said, because it creates more interest in it. She recalled a story about her aunt reading Peyton’s Place on the subway wrapped in plain paper so that it was hidden, but everyone was doing it at the time.

“Contraband is fun,” said Harris, “The idea that books contain dangerous thoughts is fascinating, that books can cause us to think is also fascinating.”

“[It’s important to celebrate the books because they] serve as an index of the things people care about over time. Independent of the intrinsic literary merit of The Scarlet Letter or Moby Dick or Huckleberry Finn, independent of this they really do give us insight of how people were feeling in a particular political moment.”