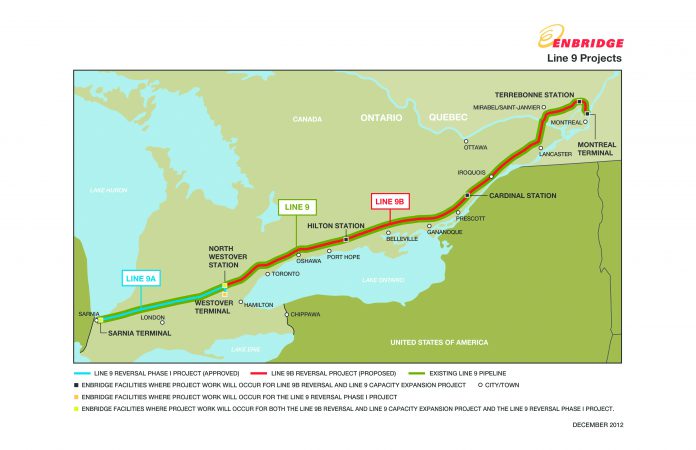

Line 9 is a 40-year-old pipeline that runs from Sarnia to Montréal, owned by Enbridge. This pipeline runs through indigenous territory, many cities, and inlets of Great Lakes.

The fact that the pipeline was first installed in indigenous territory when the people of the land were still in residential schools is a problem in and of itself, but now changes are being made to the pipeline and the indigenous people are still not being consulted on projects that impact their land in irreversible ways.

Rachel Thevenard, a student at McMaster, and Hannah Enns, a recent PACS graduate from UW, spoke to Imprint about the pipeline and what is happening.

“Enbridge applied to the National Energy Board in 2014 for three things to happen,” Enns began. “First, they wanted to reverse the flow and have the oil run from Sarnia to Montréal. Second, they wanted to change its content from crude oil to tar sand bitumen — which is sourced in Treaty 8 territory in Alberta.”

Thevenard added, “At 11 degrees Celsius, tar sand oil is as hard as a hockey puck. So it is diluted with bitumen, which is toxic and corrosive and is known to cause 95 per cent corrosion on the brand new pipe which is designed to carry it.”

Enns continued, “The final thing they applied for was an increase from 240,000 to 350,000 barrels a day. In October 2014, the National Energy Board approved the application and in December 2015, Enbridge began ‘construction’ to make it look like they were switching valves. This is when they began pumping the diluted tar sands oil.”

Thevenard spoke about the construction that was done to the line prior to the tar sand being transported. “It is industry standard to do tests with water and chemicals at higher than normal pressure to see if there are any irregularities in the pipe. Enbridge calls these irregularities, such as cracks, ‘features.’ Enbridge refused to do this test. Their reason was that the test would hurt the pipeline. Somehow highly pressurized corrosive and toxic tar sands are okay; but water will cause damage? So to compromise, the National Energy Board made Enbridge test segments at a lower pressure than mandated.”

“Line 9 crosses 18 First Nations, over 100 cities and towns, all tributaries of Lake Ontario and other Great Lakes, and the St. Lawrence river,” Enns added.

Line 9 isn’t the only one of its kind in the world. In fact, it has a twin: Line 6B. Enns said, “Enbridge switched the content of the pipe in 2010, and in 2012, the largest in-land spill happened. Line 6B leaked into the Kalamazoo River in Michigan spilling 300 litres of tar sands bitumen. Instead of floating, this oil sinks, making it impossible to clean up.”

Thevenard added, “Enbridge spent $1 billion ‘cleaning’ it up, but [what] they did is cover it up with sand. The river has since been opened for use and now when you go to the bottom and stir the floor of the river oil rises to the surface. Richard Kuprewicz, a pipeline safety expert has said that Line 9 has a 90 per cent chance of rupturing in the first five years of running.”

Having already been operational for one year, there are only four years left on that timeline.

Thevenard said, “It’s not a question of if this will happen, but a question of when. The likelihood of Great Lakes contamination is very high.”

There are many important people involved in the resistance of this pipeline, which includes five shut-offs to date.

Enns spoke about the different forms of resistance, “Within the region, there was a campaign in 2014 called ‘Waterloo Against Line 9.’ There is also Aamjiwnaang Sarnia Against Pipelines (ASAP), which is an outspoken group in the community where the pipeline originates just south of London. They engage in community education, spreading news about spills, and shutting off the pipeline. Currently, Chippewas of the Thames First Nation are engaged in a court battle, which takes place on Nov. 30. This case will set huge precedent about what can happen on treaty territory. This constitutional challenge states that the National Energy Board does not have the right to represent the government or any Indigenous group as there needs to be consent from the people of the land. It also outlines that the discussion about land needs to involve the First Nations people and all treaty holders (which is already stated in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms).”

Photo courtesy Hannah Enns.

The court case will cost the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation people $500,000. Enns and Thevenard, along with a few others, are currently doing classroom talks, bucketing at all events, and handing out flyers all over the city to help raise money to cover the costs. Their efforts are part of a larger fundraising effort across Ontario.

Here, in KW, there will be a benefit concert Nov. 5 from 2 to 6 p.m. featuring traditional Indigenous music and local Juno nominee, Alysha Brilla.

Brilla spoke to Imprint about the cause and the event. A music writer and producer for 12 years, Brilla currently resides in KW, but her work has taken her worldwide. She described her music as “a combination of what I like to listen to including, Amy Winehouse and Bob Marley,” as well as what her parents would like — “white Canadian folk music” and Indian music.

Brilla promotes messages of gender equality and social movements in her music. She believes in the cause being promoted at the benefit concert because she is part of this land and the community. “The government says that it cares about indigenous people and their rights, so let’s see something happen. I will be there [in Ottawa] on Nov. 30 with my guitar and drums, doing what I can.”

Enns has been involved on and off since 2014, since the National Energy Board hearing. She said, “It’s important to be involved in the social movements where you are living. Line 9 affects the water that I drink and solidarity is in direct support of the Indigenous people of the land that I am on right now. The different 18 First Nations people affected by this have not consented to this. For me this is about where I am and what are the causes need to come out right now.

As a settler, someone not from this land, I need to take direction from the people who are fighting the violence that continues to happen on this land.”

Thevenard found out about the cause in 2012 and thought it was absurd. She started planning to run the length of the line in 2013, and from Dec. 4 2015 to Jan. 6 2016, ran the 830 km length of the Line 9. “I would echo a lot of what Hannah said. We need to take direction from the people whose land we are on.”

Thevenard and Enns encouraged concerned students to follow movements against Line 9 on social media. The Chippewas Solidarity Facebook page also has an event for anyone to join the cause on Nov. 30 in Ottawa.

Enns said, “Bring it to different organization bodies. Faith groups, teams, clubs, and do what you can. Host a movie night or board games night and pass around a bucket — play Settlers of Catan and we are talking about this idea of settlers on land and let’s talk about this issue. Or host a meal and have everyone donate $5.”

Imprint reached out to Enbridge for a comment and was able to talk to Eric Prud’Homme, senior manager, stakeholder and aboriginal engagement, who said that the contents of the pipe were reversed in 1998 and the re-reversal was done as per customer request in 2014. When asked about the contents of the pipe Prud’Homme said, “Our shippers are the ones who make the decision for what they need transported … as long as it meets the standards set by Enbridge.”

Prud’Homme said, “As this is still a matter to go before the courts, we are very limited in what we can say publicly on the matter. We are not in a position to speculate on any future impacts to the operations of the line, but currently the line is operating normally. We are always willing and frequently do engage with Indigenous communities above and beyond what is required by regulators to build trust and address any concerns or input they may have with our projects or operations. Irrespective of the outcome of the supreme court appeal, Enbridge is absolutely committed to fostering a strengthened relationship with the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation built upon openness, respect and mutual trust, and to working through outstanding issues to find mutually agreeable solutions. We will continue our efforts to engage with Indigenous communities above and beyond what is required by regulators to build trust and address any concerns or input they may have with our projects or operations.”

Enns responded to what Enbridge said about fostering relationships and the operation of the line. “The line is not operating properly because it has had 35 reported spills in its life, but they have a habit of not reporting spills. In practise they do not foster relationships with Indigenous people because they do not have an open dialogue, with either the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation or any of the other First Nations groups.”